I have this tendency to be most critical of the groups that I’m part of. You see this a lot in terms of my thinking about the Democratic Party. But I dare say you see it most of all with my thinking about atheists. And there is a lot to dislike about the modern atheist movement. I am an atheist in the Arthur Schopenhauer tradition. Much of modern atheism is intellectually vacuous. But as popular movements go, it is still pretty good. There isn’t likely to be a mass movement that I have any less criticism of.

I have this tendency to be most critical of the groups that I’m part of. You see this a lot in terms of my thinking about the Democratic Party. But I dare say you see it most of all with my thinking about atheists. And there is a lot to dislike about the modern atheist movement. I am an atheist in the Arthur Schopenhauer tradition. Much of modern atheism is intellectually vacuous. But as popular movements go, it is still pretty good. There isn’t likely to be a mass movement that I have any less criticism of.

Probably the best aspect of modern atheism is that there is a strong current of humanism in it. I think it is the case that people like Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens are admired despite being torture proponents, not because of it. What’s more, I don’t so much see myself as part of the atheist community in the sense that I read atheist blogs and go to atheist conventions. I see myself as a member of the growing numbers of people who just aren’t religious. And by and large, this is a mighty fine group.

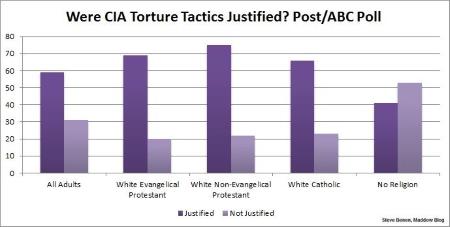

As regular readers know, I found the recent release of the torture report as upsetting as it was unsurprising. So I was somewhat pleased to read Steve Benen’s The Week in God today. It’s focus was on a new Washington Post/ABC News poll on attitudes about torture. It confirms the results of a 2009 poll by Pew. As you’ve probably heard, Americans are overwhelmingly in favor of torture. Of those polled, 59% were just peachy with what the CIA did; only 31% had a problem with it. Obviously, that was not what pleased me.

This poll subdivided people by their religious affiliations. So Benen put together the following graph that sums up the main categories:

Benen pointed out that people with “no religion” were pretty much the only group in the report that were against torture. I wish the numbers were better than they are, but they are far better than average. And the major Christian groups are all worse than average. It’s disgusting, but again, unsurprising. It goes along with my primary complaint against modern American Christians: their religion is all culture and no theology. The one thing they absolutely believe is that people like them are “good” and people not like them (eg, Muslims) are “bad.” Thus they don’t really care. After all, it’s not like anyone is suggesting burning the evildoers alive. (Not that they would be against that either.)

As much as I’m pleased that we non-believers demonstrate more humanity than average, this information is profoundly disturbing. We are, after all, an almost 80% Christian country. And the only takeaway from that is that Christianity is “right” and that Christians are oppressed whenever someone says “Happy holidays!” to them. We live in a sad world.

Over at The Monkey Cage, Elizabeth Suhay wrote some much needed perspective,

Over at The Monkey Cage, Elizabeth Suhay wrote some much needed perspective,

There once was a time in history when the limitation of governmental power meant increasing liberty for the people. In the present day the limitation of governmental power, of governmental action, means the enslavement of the people by the great corporations who can only be held in check through the extension of governmental power.

There once was a time in history when the limitation of governmental power meant increasing liberty for the people. In the present day the limitation of governmental power, of governmental action, means the enslavement of the people by the great corporations who can only be held in check through the extension of governmental power. On this day in 1921, the great American film director

On this day in 1921, the great American film director