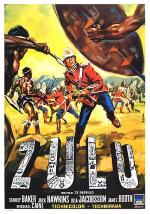

Last night, I watched the 1964 classic, Zulu. I’ve always really liked the film, but it also seems somehow racist. I add the modifier there, because the film goes out of its way to portray the Zulu with a great deal of dignity. And having watched the film again, I am of the opinion that it isn’t racist, although it is Anglophilic: it tells the story entirely from the standpoint of the British. I don’t think there is anything wrong with that — especially given when the film was made. What I think is most interesting, however, is that an equally great film could be made entirely from the Zulu perspective.

Last night, I watched the 1964 classic, Zulu. I’ve always really liked the film, but it also seems somehow racist. I add the modifier there, because the film goes out of its way to portray the Zulu with a great deal of dignity. And having watched the film again, I am of the opinion that it isn’t racist, although it is Anglophilic: it tells the story entirely from the standpoint of the British. I don’t think there is anything wrong with that — especially given when the film was made. What I think is most interesting, however, is that an equally great film could be made entirely from the Zulu perspective.

I love the stories of family squabbles, especially when they have consequences far outside the family. Cetshwayo kaMpande, the king of Zululand, was a good ruler. The British were the aggressors in the Anglo-Zulu war. And overall, the Zulu were doing quite well. But Cetshwayo was not out to create a new empire. He was just trying to hold onto to his own kingdom. Even after his success at the Battle of Isandlwana (the subject of the mediocre film Zulu Dawn), he wanted to make peace with the British. And he might have been successful if it weren’t for his half-brother, Dabulamanzi kaMpande.

It was Dabulamanzi who instigated the Battle of Rorke’s Drift — the subject of Zulu. Rorke’s Drift was outside of Zululand and Cetshwayo did not want to attack outside of his own land. That’s not to say that Dabulamanzi was disloyal. In fact, he was very loyal. He was just younger and less wise. It’s not clear what he really thought to accomplish at Rorke’s Drift. A victory would have meant nothing compared to the victory at Isandlawana. As it was, the British didn’t win the battle so much as survive. That brings up the important point about the ending of Zulu.

The most beautiful part of the film is where the Zulu sing a song in preparation for a huge attack. In response, the British sing, “Men of Harlech.” It is a beautiful moment that has no historical basis. But who cares? It is followed by the Zulu attack. The British fall back and form three lines of fire. And after much sound and fury, the British are left standing in front of a sea of death Zulu warriors. It is an amazing bit of filmmaking, switching from the lyricism of the singing scene to the brutality of the attack.

After this, the film cuts to three hours later where we learn that the Zulu have not attacked again. Then the Zulu appear on the hillside — thousands of them. The British don’t even try. It is over. But instead of attacking, the Zulu sing a song honoring them as fellow warriors. And then the Zulu go on their merry. It works rather well as an ending to the film, but it isn’t what happened. In fact, the Zulu just disappeared because they were short on supplies, with many wounded, and far from home.

But Rorke’s Drift had great public relations benefit for the British. I question whether the British would have continued on with the Anglo-Zulu War without this “victory” — especially with Cetshwayo’s attempts to broker a peace. But it’s hard to say. In terms of imperialism, the British were not nearly as bad as many. But that’s just a function of how bad others — notably my own Portuguese ancestors — were, and not of the British being great.

Another interesting thing about the battle is what happened to the British soldiers who fought in it. Most of them died quite young. Lieutenant Bromhead, for example, died of typhoid fever at the age of 45 while serving in India. But the situation was much worse for lower ranks. One of the men, William Jones, ended up pawning his Victoria Cross. He died in a workhouse. But in some ways, he was lucky — living into his 70s. The most extreme case was that of Ferdinand Schiess. He couldn’t find work — a common situation for the men who fought at Rorke’s Drift. A few years after the battle, he was discovered by the Royal Navy on the streets of Cape Town — starving. They saved him, but he died on the journey back to England. He was 28 years old. (That is the age that the hero dies in Jude the Obscure — written around the same time.)

I bring this up because it shows the way that the powerful treat the people. It doesn’t matter if they are enemies (reluctant though they may be) or friends — even heroes. They are all expendable.