The guys at the The Q Filmcast do a podcast every week where they pick a film on Netflix to discuss. It is a surprisingly good show. There are five of them and they never seem to agree. Thus far, I have agreed the most with their producer Adam Rodgers, who the rest of the gang seem to think is a cinematic philistine. I don’t consider myself a philistine, but I do constantly rebel against what I think of as the professionalization of mediocrity. If you have the money to hire professionals, it is trivial to tell a standard story in a standard way. In general, I’m more into psychotronics and more generally personal art that is thrilling but often inconsistent or worse.

The guys at the The Q Filmcast do a podcast every week where they pick a film on Netflix to discuss. It is a surprisingly good show. There are five of them and they never seem to agree. Thus far, I have agreed the most with their producer Adam Rodgers, who the rest of the gang seem to think is a cinematic philistine. I don’t consider myself a philistine, but I do constantly rebel against what I think of as the professionalization of mediocrity. If you have the money to hire professionals, it is trivial to tell a standard story in a standard way. In general, I’m more into psychotronics and more generally personal art that is thrilling but often inconsistent or worse.

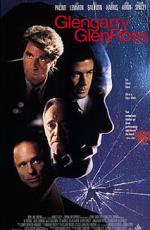

So when I heard that the Q boys were going to watch Glengarry Glen Ross, I was excited. I’ve been meaning to watch it for years, but I hadn’t gotten around to it. So I curved up with it Friday night and watched. It is everything that you expect from a David Mamet film. And if you like him, I don’t see how you can go wrong. Unfortunately, I don’t like Mamet. That’s not to say that I always hate his work. For one thing, when I read American Buffalo when I was a kid, I thought it was fantastic. But that was my introduction to him. Since then, I think everything that Mamet has to offer is on display in that play.

I remember reading that in his original script for The Verdict, Mamet ended without the jury coming back. I admire this. The story is about the personal redemption of Frank Galvin. It doesn’t matter that he wins the case in practice; we’ve seen that he has won in the eyes of Galvin. But it does have a resolution because Mamet is constrained by Barry Reed’s novel. When Mamet is not constrained by someone else’s story, he doesn’t bother to even come up with a story. Generally, he writes stories that are “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

This is entirely true of Glengarry Glen Ross. It tells the story of four salesmen and an office manager. The owners of the company have decided to have a sales contest where the top two win prizes and the bottom two are fired. We only get two days into the month before the entire office is destroyed. As is typical of Mamet, he seems not at all interested in the absurdity of the situation. Nor does he seem to be aware that ultimately the owners are to blame—you make people too desperate and they will turn on each other. Of course, they already have, just in smaller ways. We learn, for example, that the office manager has been giving out good leads to agents he likes and bad leads to agents he doesn’t. In fact, my reading of the script is that the agents’ sales are totally determined by the leads given to them, just as they allege throughout the film.

All of this conflict is in the service only of the conflict itself. The thematic core of the film comes when a once great salesman (Jack Lemmon) asks the office manager (Kevin Spacey) why he is trying to destroy him. The office manager says, “Because I don’t like you.” That’s the tautological message of the film: people are cruel because people are cruel. I don’t doubt that Mamet sees the world like that. But that isn’t the way the world seems to me. People are cruel to each other mostly because they get an advantage from it. Mamet’s take on the world is the simplistic mentality of pubescent boys who haven’t learned how to manage their hormones.

Along with the unrealism of the plot, we have the highly stylized Mamet dialog. In small doses, it’s fine. But I’ve been inundated with it for decades. It hasn’t grown. It’s the same thing we always get from him. And sadly, it is the same thing we get from a lot of writers who have followed after him. If it weren’t for how foul it all is, I’m sure critical opinion on it would have changed and more people would admit to how annoying it is. But okay, it is what it is. What is is not is realistic.

I know that Glengarry Glen Ross would work much better as a play. That was especially true of the scenes between Moss (Ed Harris) and Aaronow (Alan Arkin). These are very funny, fast paced dialogs. But the director James Foley decided not to do them in a two shot or similar. So we cut back and forth between the characters very fast. It not only makes one’s head spin, it distracts from the dialog. There is no continuity. I have no idea why it was done that way. I am rarely even tempted to say something I don’t like is wrong, but here it is hard to escape that conclusion.

The film does not expand itself very much from the play. At times, I think that works rather well. The opening in payphones worked really well, for example. It reminded me of the art direction in the 1996 version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. But the vast majority of the film takes place in the office. And other than it looking totally like something built on a sound stage, it had nothing of the otherworldly feel of the other locations.

There are things to admire in the film, however: mostly the acting. It is great. Kevin Spacey as the small minded and hateful office manager was wonderful. Al Pacino gave a slightly muted performance, which was perfect for the flamboyant “closer” of the office. (Am I saying that Pacino usually over-acts? Yes!) Lemmon, Harris, and Arkin were all excellent. Alec Baldwin tried very hard but was not properly supported by the direction. The standout performance was Jonathan Pryce in a small role with almost no dialog. Throughout the film, I felt he was the human ombudsman, looking on in horror, “What kind of creatures are you anyway?”

I know that a lot of people will like Glengarry Glen Ross. And there is no doubt that Mamet is probably more in tune with American attitudes toward drama than he ever has been. But I think a close viewing of the film shows its problems. It is ultimately empty socially and spiritually. It has nothing to say and it says it in the most offensive way it can. And as much as that is modern America, I don’t want to be reminded. So in the end, my feelings about the film are the same as Adam’s: I just don’t like it; it makes me feel bad without any enrichment. Regardless of how we dress up our feelings about a film post facto, that’s what it all comes down to. It would seem that Adam is just being more honest than the rest of us.

Now you know that I’ve earned the right to say Lawd!!! Wow Frank, your dissection of this film is certainly done so with intelligence. Not sure why you’ve found the concept and situation absurd? Not sure what warms your heart, apparently Rosencrantz and Guildenstern – which AGAIN makes me say… LAWD!!! Seriously, thanks again for the nod! We really appreciate the attention. You’re awesome

I remember watching this with my parents. My usually, but every now and again not so much, uptight conservative parents. I had seen a preview of it that looked interesting and rented it. Is the F-word count over or under the N-word count in Django Unchained? Anyway, their take on it was that it was an updated Death Of A Salesman. Sadly, the Steak Knives speech has become, like Gordon Gekko, morally inverted and celebrated by American corporate culture.

@Michael – It’s absurd in the same way [i]The Apprentice[/i] is absurd. Companies don’t just decide to fire half their commissioned staff unless they want the company to implode as seen in the movie. It’s an absurd setup to see how the characters react. But I largely agree with what you said in the podcast. I’ve known a lot of people who think this is the way things are done. I used to manage the IT department for mid-sized investment company. I saw a lot of whipping up the troops. But ultimately, the people who succeeded where just the ones who worked hard at developing contacts. The best people quickly moved on to better companies. But in the film, the real problem the company has is the office manager who is making up for whatever by building his own little fiefdom rather than growing the business. In the end, the office is left with no leads and only the best and the worst salesmen. The play seems to provide more motivation for the office manager. It also ends with the implication that the office manager stays. That makes more sense to me.

I don’t mind an absurd setup. But it isn’t edify. Reflecting on it now, I think that Mamet is not just reflecting the culture. He is part of making it worse. Tom Stoppard is not. ;-)

@Lawrence – Every script has a perspective. Perhaps what I don’t like is that Mamet has a social Darwinian perspective. The Steak Knives speech isn’t in the play. But I’m glad you brought it up. Even I can get into the Gekko speech. He’s Machiavellian. I’m not sure what Blake is doing. "You drove a Hyundai to get here–I drove an eighty-thousand dollar BMW"? Really?! That’s just pathetic. I look at that guy and I think: you’re just some loser who thinks he’s someone because he flies first class. If money is the only thing you care about and a BMW is impressive to you, you’re shit. You aren’t even rubbing shoulders with the true elite. You’re a failure.

But the problem is that either Mamet is portraying Blake as an ideal, or he is portraying everyone as losers. It is a bleak vision of the world. And it is a bleak vision that he has written any number of times. At some point, it stops being art and becomes commerce. For Mamet, I would say that happened sometime in the 1970s.

It may be worth noting that Mamet has been a conservative for some years now. He describes his conversion experience in this barely sensible essay:

http://www.villagevoice.com/2008-03-11/news/why-i-am-no-longer-a-brain-dead-liberal/full/

What stuck out for me is Mamet saying he was listening to NPR and thinking "shut the fuck up." Shades of Chris Hitchens experiencing his "come to Jesus" moment reading online commentaries about the terrorist attacks against New York and Washington.

I could find annoying self-indulgent material from every viewpoint. I don’t bother. It means nothing. A few years back, I recommended a wonderful Joe Sacco book about the Baltic wars, "Safe Area Gorazde", to a Croatian-heritage friend of mine. He was excited to get the book. Then he went to some online bookstore and saw comments that made him wither. Didn’t buy the book, because people he doesn’t agree with liked it. Even though I told him, as a friend I’ve known for 20+ years, that he would like it a lot. He didn’t want to be tainted by association with the wrong lot, I guess.

The last thing I saw by Mamet was his film "Redbelt," which seemed to say that few people have a sense of honor transcending personal gain (true enough) and women never do. I won’t see anything he wrote ever again.

I find it curious that "conservatism" is the philosophy of choice for people who think they are done being idealists with their heads in the sand, that they are ready to see the world realistically. That demonstrates some seriously insular thinking. You can’t make America a less batshit cruel society, even though other societies have succeeded quite well at reducing the impetus for cruelty. You might as well be a defender of Catholic child molesters saying nothing else is possible, a defender of Saudi society saying no equality for women is possible, a defender of American slavery, etc. "Realism" in this light is nothing more than saying "I like what I have and I don’t want anyone to change it."

Maybe the moral here is never give literary accolades to people; it tends to make them think they are Deep Thinkers, instead of talented writers.

@JMF – I think a lot of people get success and then try to justify that they deserve everything they have. They eliminate the power of luck. I don’t see how anyone can claim that being successful in this society shows anything but that you have the right personality and abilities to succeed in [i]this[/i] society. There are plenty of other ways to organize society.

I’ve become far more practical as I’ve grown older too. I think the problem with Mamet and Hitchens is not that they became practical, it’s that they became assholes. Or maybe always were, but got comfortable enough with it to go public.

You hint at another aspect of Mamet: he apparently doesn’t like women very much.