Last week, This American Life produced an episode Confessions. The show primarily consists of two stories. The first is about a detective who learns that he had unintentionally created a false confession. The second is about Jeffrey Womack, whose life was haunted by a murder allegation that he refused to talk to the police about. What is interesting in both cases is the reactions of other people and how they second guess what happened. It is the ultimate example of blaming the victim.

Last week, This American Life produced an episode Confessions. The show primarily consists of two stories. The first is about a detective who learns that he had unintentionally created a false confession. The second is about Jeffrey Womack, whose life was haunted by a murder allegation that he refused to talk to the police about. What is interesting in both cases is the reactions of other people and how they second guess what happened. It is the ultimate example of blaming the victim.

In the false confession case, the officer is so convinced that the suspect did the crime that he feeds her details to parrot back. The case falls apart after the defendant recants and the physical evidence falls apart. But of course, the officer is sure that she was somehow involved. It is only ten years later when he looks back on the “confession” tape that he sees the problem. He says to her, “Let me refresh your memory.” And then he gives her credit card receipts that allow her to know basically all of the details of the case.

What’s most interesting here is that the officer now lectures to other police officers. But he says that he can’t give a lecture on preventing false confessions because no one will show up. So he has to lecture on interrogation tactics and then just throw in a bit about false confessions at the end. As he points out, there is nothing that the police believe as strongly as the fact that innocent people will not confess to a crime they did not commit. This is despite the fact that there are many notable cases like the Central Park 5.

Police work ought to be like science, and under the best of circumstances I’m sure that it is. The evidence should lead the detective to a conclusion. But most cases are obvious. As Verbal says in The Usual Suspects, “To a cop the explanation is never that complicated. It’s always simple. There’s no mystery to the street, no arch criminal behind it all. If you got a dead body and you think his brother did it, you’re gonna find out you’re right.” But that leads to detectives filtering out exonerating evidence. For example, in this case, the woman under investigation was in a homeless shelter during the crime, but the officer didn’t even check until months later after she had recanted her confession.

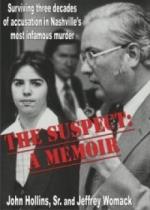

The second case is one where the police went after a teenager, Jeffrey Womack, for a rape and murder. His lawyer told him not to talk to the police or the media. Again, the case against the kid fell apart because he wasn’t guilty and he had a decent lawyer. But for 30 years, until the actually killer was convicted, he lived under a shadow. Everyone just knew that he did it. But now that there is no doubt of his innocence, no one in the police department thinks they were wrong to harass him. They all think the same thing, “None of this would have happened if he had just talked to us!” Most people in the area think the same thing.

The story interviewed a reporter who said more or less, “I just don’t understand it; if it had been me, I would have been shouting my innocence from the rooftops!” You get that? Because this guy was not behaving the way she thought she would have, it must mean that he’s guilty. I noted this some months ago about the coverage of Debra Milke. Long before people are convicted in court, they are convicted by the media, using the same snap judgments that usually are correct. But “usually” really isn’t good enough. I wouldn’t want to be convicted of murder because a reporter or a police officer thinks I did it and is usually right about such thing.

What is fascinating about these two cases is how the victim is always wrong in the eyes of outsiders. In the first case, people think that the young woman should not have trusted the police; she should have just remained silent and nothing bad would have happened. (To be fair, the detective does not make this argument.) In the second case, people think the young man should have trusted the police. In the first case, I don’t think things would have been much different, except that she might have spent slightly less time in jail. In the second case, I suspect the young man would have spent a lot of time in jail and might have even been convicted. The fault is not with these victims but with the system itself.

Afterword

I think it is interesting that the false confession detective has made a whole career out of it. The victim’s life was destroyed.

I understand that this is more about our flawed society: our justice system, law enforcement, and the power of media to condemn just about everyone.

What I find most interesting is the fact that our own memories can be so easily manipulated. Even on a good day I don’t trust the reliability of my own memories. Under the stress of interrogation, there’s no telling to what I might confess or whom I might condemn.

I think you’re right about the falsely accused man. Clamming up might look bad, but babbling can make things much worse.

The saddest thing is that the only people who can be accused and excused are those with wealth or power.